In the wake of the Paris attacks, the mediasphere began to talk — as it always does — and much of it has been talking in circles, or at cross-purposes. Tragedy causes the exponential proliferation of polemics, creating an overheated environment in which nuance tends to suffocate.

From Twitter user @EllenKnickmeyer

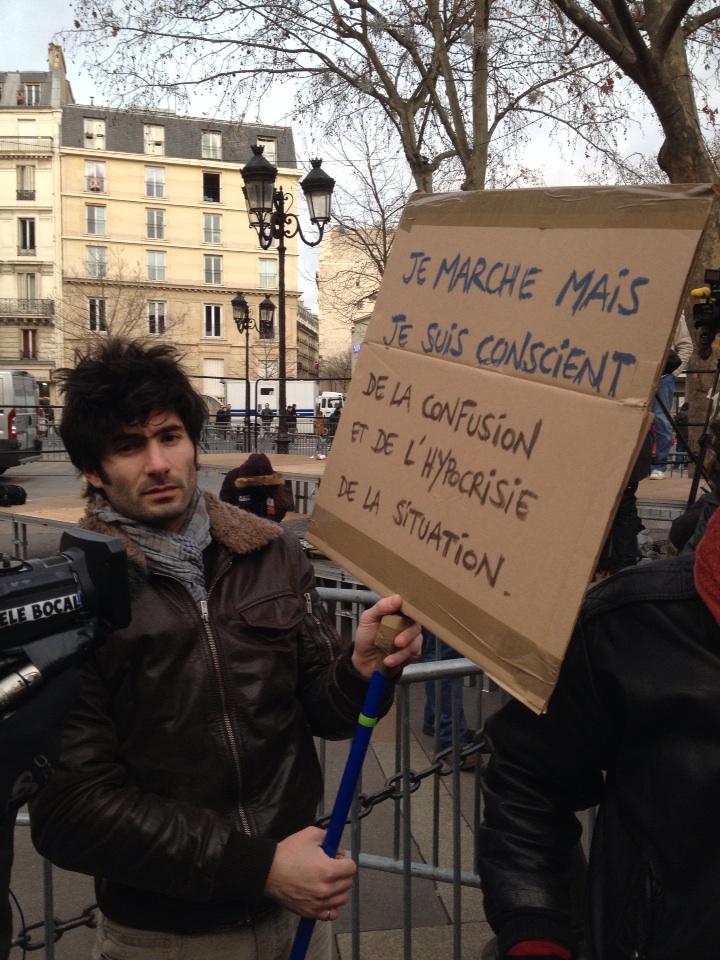

My discomfort only grew as I became aware of the idiom which arose spontaneously out of a laudable sense of sympathy for the victims of the attacks. While I understand that the meaning of an expression is its use — and that usage is determined more or less entirely by circumstance — I found myself in the awkward position of agreeing with David Brooks, who said in The Times that “[…] it is inaccurate for most of us to claim, Je Suis Charlie Hebdo […]. Most of us don’t actually engage in the sort of deliberately offensive humor that newspaper specializes in.”

I have only passing familiarity with Charlie Hebdo — passing, that is, in the sense that I have only ever “passed” every opportunity to read it, finding the headlines and the covers much too crass. No one ever said that Charlie is for everyone: Le Devoir’s Stéphane Baillargeon aptly calls the newspaper “moins satirique que vitriolique.” [EDITOR’S NOTE: That translates, roughly, as “less satirical than abusive.”] In full, honest recognition of Charlie’s style and function, it should be possible, without seeming contrarian or disrespectful, to take exception to “Je suis Charlie” on the reasonable grounds that it may be problematic in its implications. On Twitter (where sarcasm is never in short supply) one commentator expressed relief that Éric Zemmour was not amongst the victims so that he should not have to identify with a figure who is even more controversial than Charlie Hebdo.

The immediate aftermath of a catastrophe is hardly the appropriate time for hair-splitting debates over the intentional fallacy, but it is hopefully not entirely out of place to observe that caricature does not affect the powerful and the disenfranchised in the same manner. As Teju Cole wrote in The New Yorker: “The West is a variegated space, in which both freedom of thought and tightly regulated speech exist, and in which disavowals of deadly violence happen at the same time as clandestine torture. […] It is not always easy to see the difference between a certain witty dissent from religion and a bullyingly racist agenda, but it is necessary to try.”

I would never suggest that freedom of speech is not a more fundamental principle than the respect of institutions which any misguided interpreters of Islam might seek to appropriate for themselves through fear and strength of arms. On the other hand, true freedom is complex, and I worry that this incident will be instrumentalized in the great xenophobic tradition of “the clash of civilizations,” a base rhetoric of essentialized ethnic designations which has been making a comeback in the writings of popular intellectuals such as Houellebecq and Zemmour.

There is not much else which my experience and expertise allow me to say. I might add that I find the question of whether or not images of the Prophet are forbidden in Islam to be somewhat beside the point; it seems to me it should be enough to reflect that the issue of representation is superlatively fraught, though I suppose it is not my (nor anyone’s?) place to decide what should or should not be part of the conversation.