Continuing our interview with Martian Comics creator and the Sequart Organization founder Julian Darius, we move from his depiction of the prophet Ezekiel to his treatment of Lazarus and of Jesus, “The Galilean”:

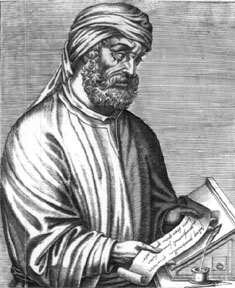

S&S: “Ezekiel” is followed by the longer, 11-page, “What Has Athens to Do with Jerusalem?” The title, presumably, comes from the writings of the Church Father Tertullian, yet the story focuses on Lazarus, the man Jesus resurrected, and Paul. What’s the connection between the title and the concerns of the story?

JD: The quote comes from a later period. But it’s key to the point of the story.

On the one hand, the story allows us to catch up with Lazarus, seeing how he’s evolved —

S&S: Since readers last saw him in issue #2 of Martian Comics, freshly resurrected by Jesus but, in effect, unable to fully live or rejoin what was his life.

JD: Right. Lazarus actually has a cameo in issue #1, but issue #2 is the first to have a story all his own. The idea is to follow up on the Lazarus story, because the Bible never tells us what happened to him. The point is that Jesus resurrected him, and it’s a miracle – but Lazarus is just a prop, really. He’s a demonstration of Jesus’s power. So I thought “what happened next” was an interesting idea, and I thought this tension – about how Lazarus is kind of forgotten, once he’s resurrected – should be part of the story.

So in issue #2, Lazarus is resurrected, but he’s been decaying a little, and these rural Jews of the first century, who were pretty superstitious, would have seen him as a supernatural thing. They’re scared of him, and he doesn’t look right. It’s not going to be like “Oh, Lazarus, glad you’re alive again, old chap!” No, there are going to be rumors, and any physical deformity or ailment was seen as potentially demonic or dangerous. That’s why Jesus ministering to lepers was such a thing. And in those days, you really needed a community to survive. So Lazarus is alive, but he’s kind of a pariah. And he sees how this is hurting his family – that, as he says, he’s of no use to them.

So Lazarus is kind of figuring out what being resurrected means. It’s not just that you came back to life. You’re different now. You look different, and you’re treated differently. Jesus does his miracle, and everyone’s impressed, but no one really follows up with Lazarus. There’s no post-resurrection counselors or anything.

Along with this, what does resurrection mean biologically? Does someone who’s been resurrected return to life and live out a normal lifespan, as if they hadn’t died? Do they get a week and then die again? Maybe resurrection’s not permanent! Or do they live forever? I think we usually don’t ask these kinds of questions, and it’s not a focus of these stories in the Bible, where the point is that Jesus is powerful because he resurrected someone – implicitly encouraging us to believe. We kind of assume that any bodily decay is healed as part of the resurrection, although that doesn’t necessarily follow. And I was interested in exploring all of this. My Lazarus doesn’t have his bodily decay healed, and whatever energy resurrected him is still in him. He’s immortal, although he doesn’t know it at first. He learns it in pretty dramatic fashion in that story.

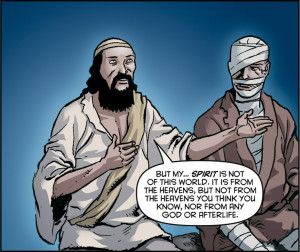

So Lazarus is alienated, not only from his community but from himself and his body. But he’s also alienated from Jesus. If you think of a miracle as basically a special effect, a demonstration, Lazarus is a walking special effect. But nobody gave him a guidebook for what’s going to happen, or how any of this works. And I think he has a sense that he’s been discarded, in a way – that Jesus has been a little cavalier about this. So he goes to talk to Jesus.

And that’s really the climax of the story, this conversation in which Lazarus confronts Jesus respectfully, and is clearly hurting. Jesus, who’s from Mars, doesn’t have all the answers. I love this idea – we always assume that someone knows all the answers, that the person behind things (whether a writer, or a politician, or a god) has satisfying and full answers for everything, but that’s almost never the way things work. Jesus is very compassionate, but he doesn’t have that guidebook either.

(Actually, in the Gospels, it’s not clear to what extent Jesus had much foreknowledge, except in versions where angels tell Mary what’s going to happen – though Mary doesn’t seem to pass this on to Jesus, nor really act as if she knows this. That’s a pretty clear sign that it, like the virgin birth, was a later interpolation into the story. In Paradise Regained, Milton uses the idea that Jesus doesn’t have a roadmap for himself to dramatize this questioning, which I think makes a Jesus who’s a lot more human, more approachable, and can actually serve as an example for us to follow. I love that honest questing for answers. And that’s where Lazarus gets to, by the end of the story.)

Although Jesus can’t give any answers about Lazarus’s condition, he gives the answers he can about Mars. It’s a very Star Trek moment, there in the climax, where Jesus is trying to explain Mars in a way Lazarus might understand. Incidentally, this kind of ties into the Gnostic concept of Barbelo, which is usually depicted as a kind of Holy Spirit-esque emanation of God but which is sometimes depicted more literally, even in ways that seem like it’s maybe an outer-space location. In the apocryphal Gospel of Jesus, Judas is the only disciple who “gets it,” and he tells Jesus that he knows Jesus is actually from Barbelo. Mars isn’t Barbelo, but this weird sci-fi moment, in which someone is introduced to things they can’t possibly understand or imagine, actually has roots in religious literature.

At the end of that story, Jesus kind of invites Lazarus to join his disciples, but Jesus is killed, and Lazarus doesn’t fit in with the disciples. So he leaves to find his own way. He’s already learned that he can’t go back to his old life. He has to grow. He’s had this encounter with Jesus, and in some ways been closer to Jesus than Jesus was with the disciples. But with Jesus gone, Lazarus can’t stay there either. And he has the courage to find his own way, in part because of the strength he’s acquired from this whole experience. I can’t imagine Lazarus before his resurrection, whose concerns were very local, having this courage. He’s grown as a character.

S&S: So, the Lazarus of issue #2, resurrected by the Jesus of issue #1, meets Paul now in issue #3 and is exposed to Athens.

JD: And, as part of this, we also get to see a bit of Athens and its culture, which changes Lazarus. And I think it’s a very interesting idea that someone who’s immortal would live to see events they experienced become misremembered, or appropriated by one cause or another. Lazarus is narrating, so we’re in his mind to a certain extent.

But what Lazarus doesn’t know is that he’s witnessing the birth and early evolution of Christianity. We know that, but he doesn’t. At the end of the story, Paul leaves Athens, and Lazarus imagines that we won’t hear about Paul or his beliefs again. It’s a reasonable assumption — Paul hasn’t done well in Athens, and there’s no reason to think what he said there would go on, continue to evolve, and wind up taking over the empire. No one would have imagined that.

And there’s this idea, in the story (and this is historically responsible), that Athens was this kind of proving ground for philosophers. It was like coming to New York City. If you could make it in Athens as a philosopher, you could make it anywhere. Paul didn’t make it. He just didn’t. In the Bible, there’s this kind of half-hearted attempt to say he was successful, and that’s reflected in my story, but historians agree that he wasn’t a hit there. He was still evolving his understanding of Jesus, and what’s recorded (even in the Bible) of what he says in Athens is just not very good. In Athens, you can’t just stand on a proverbial soapbox and say, “You’re ignorant!” Which is really the sum of what Paul’s argument. He doesn’t really have an argument. He just says Athenians are ignorant, and they should worship his god. But Athens had its own concept of a creator-god, and it’s not something to get riled up and yell over. Paul is not successful in Athens. He also can’t adapt to Athenian culture, and he’s essentially put on trial, where he basically recants — all the stuff about Jesus, which is why he was put on trial, he just drops. It’s right there in the Bible, actually, if you read carefully. And then Paul leaves. So there’s this sense that he — or his followers — are embarrassed. In the story, Lazarus concludes that what Paul was offering wasn’t philosophy, and he’s indisputably correct.

And if you look at Christian history, that anti-intellectual strain embodied in the Tertullian quote starts very early on. The whole point of that quote is that faith has nothing to do with logic. You can’t argue about it, you just have to believe it. Screw those academics, who think they’re so much smarter. Screw those philosophers, who think they can find logical flaws. None of this matters. “We sacrifice the intellect for God.” That’s been core to Christianity, if we’re honest, from very early. We like to imagine that Christian hostility towards the academy and science is new, and its current incarnation is obviously fundamentalist, a reaction against modernity. But putting Galileo on house arrest wasn’t a single mistake made by the Catholics. As soon as Christianity gained power in the Roman empire, it started burning books. That’s why Europe later had to get so many of its own ancient pagan works from Muslim libraries. We like to praise the scholastics, but the whole reason they were revolutionary and controversial was that they went against the entirety of Christian history. They’re an exception, and that’s why they’re celebrated — they fundamentally changed Christianity. Seriously, “philosophy” for a millennium meant squaring the circle, trying to make contradictions make sense — basically, philosophy was reduced to earning a Marvel No-Prize for “fixing” continuity errors. And if we know anything about European history, we know this is coming. And it’s embodied in that Tertullian quote.

And if you look at Christian history, that anti-intellectual strain embodied in the Tertullian quote starts very early on. The whole point of that quote is that faith has nothing to do with logic. You can’t argue about it, you just have to believe it. Screw those academics, who think they’re so much smarter. Screw those philosophers, who think they can find logical flaws. None of this matters. “We sacrifice the intellect for God.” That’s been core to Christianity, if we’re honest, from very early. We like to imagine that Christian hostility towards the academy and science is new, and its current incarnation is obviously fundamentalist, a reaction against modernity. But putting Galileo on house arrest wasn’t a single mistake made by the Catholics. As soon as Christianity gained power in the Roman empire, it started burning books. That’s why Europe later had to get so many of its own ancient pagan works from Muslim libraries. We like to praise the scholastics, but the whole reason they were revolutionary and controversial was that they went against the entirety of Christian history. They’re an exception, and that’s why they’re celebrated — they fundamentally changed Christianity. Seriously, “philosophy” for a millennium meant squaring the circle, trying to make contradictions make sense — basically, philosophy was reduced to earning a Marvel No-Prize for “fixing” continuity errors. And if we know anything about European history, we know this is coming. And it’s embodied in that Tertullian quote.

I can’t prove this was the moment where Christianity veered in that direction. But it makes sense.

So there’s this whole subtext to the story, in which Lazarus isn’t only watching the birth of Christianity without knowing it. He’s witnessing the moment when Paul tried to establish Christianity (which was still a work in progress) as a philosophy, and he failed. And there’s a bitterness there. The title reminds us that there will be consequences for this, that Christianity is going to not only survive but become hostile to philosophy. It certainly won’t be trying to accommodate or prove itself to philosophy ever again. So what we’re witnessing is a key event in Christian history, which will have unintended consequences — consequences Lazarus can’t see yet, but to which the title alludes.

And that’s the final line of the story: “You never know how you’re going to influence people.” Lazarus thinks it’s a line that’s about how he’s been personally influenced by Jesus, and we know he’s been greatly influenced by Athens too. But the line is also about how Athens has influenced Paul, and through him Christianity.

Thus the story’s title.

S&S: When he finds Paul, Lazarus seems disturbed by what he feels are inaccurate stories of Jesus being told. To himself, Lazarus notes, “I recognized almost nothing of the Jesus I knew in his words. His life had been appropriated. Deformed. But I said nothing.” How much of your own feelings on Christianity is being voiced here by Lazarus? To what degree does Lazarus represent you?

I don’t know, honestly. I’m sure a lot of readers assume these are just my thoughts, although they’re certainly the thoughts of a lot of Christian scholars and historians. But I’d like to plead that these aren’t really my thoughts, for a couple of reasons.

Now, in the story, it’s clear that Jesus resurrected Lazarus. I don’t believe that, and historians, of course, don’t believe that. We see Jesus in Martian Comics #1, and he’s trying to enlighten people. That story focuses on the Beatitudes, on Jesus’s rejection of and by his biological family, and generally liberal stuff like not casting the first stone. In the first Lazarus story, in Martian Comics #3, Lazarus tells us that Jesus’s disciples didn’t really know how to handle his death, and they seemed to think he was going to throw Rome out of the Holy Land. I think that’s a lot more historically accurate than the very liberal Jesus I depicted. Jesus says, in the Gospels, that the world is going to end in the lifetime of those hearing him (in fact, that’s why the medieval Catholic church invented the idea of the Wandering Jew). And it’s pretty clear that one of the expectations of the messiah, especially in the rural places Jesus visited (he avoided the big cities), was that he was going to start a revolution and throw the Romans out. That was what people expected, and I don’t personally believe that the historical Jesus didn’t have this aim. It’s pretty clear that his followers believed this. I mean, he was followed by zealots, who were armed revolutionaries, and that wouldn’t have been the case if he was telling people “my kingdom is actually in Heaven, guys.” Then Jesus dies after heading into Jerusalem on a donkey, in order to consciously fulfill prophecy, which sent a clear message of “yes, I’m the messiah, and I’m finally coming to Jerusalem to throw the Romans out.” Everyone would have understood this message, at the time. Then Jesus follows through, bringing his armed followers to the temple, where he assaults the money-changers. Of course, his followers saw the temple Jews as Roman collaborators. This was a revolutionary act, and the Gospels have him saying in this context that he comes not to bring peace but a sword. And it’s because of this that the Romans — not the Jews — arrested Jesus and executed him publicly. He was a revolutionary. Personally, I like the Jesus I depicted — Lazarus’s Jesus. He’s kind of a liberal Jesus most of us would like. But I suspect that I wouldn’t like the real Jesus, if I’m being honest. For one thing, he wasn’t concerned with gentiles. I would have no time for his eschatology, for his revolutionary zeal, for all this weird, first-century rural Jewish prophetic stuff. I don’t think most people today would.

So when Lazarus says that he doesn’t recognize the Jesus whom Paul is talking about, Lazarus is remembering a Jesus whom I don’t believe is historically accurate.

But the idea that Paul’s preaching was at odds with the historical Jesus isn’t in much dispute. Jesus’s followers were still around, and they still considered themselves Jews. It was Paul who had an epiphany in which God told him this sect of Judaism was suddenly for gentles too — an unprecedented idea in Judaism, and one both the historical Jesus and the Jesus as recounted in the Gospels clearly and unambiguously disagreed with. Then Paul goes around to the Greco-Roman world, preaching his Jesus for all people. Reading Acts, you can see how this vision of Jesus evolved. Is he God? Is he the Son of God? What does that mean? Paul’s still working this out, to some extent, in Athens. Historians recognize this, and it’s not really in dispute. Also, Paul was summoned back by Jesus’s followers, who objected to what Paul was teaching. They knew Jesus, and Paul was taking liberties. Which isn’t a surprise, since Paul was preaching to a Greco-Roman audience that wasn’t immersed in Jewish prophecy and thinking, which Jesus clearly was. Most historians wouldn’t put it like this, but Paul invented Christianity. It was his idea to break completely with Jewish tradition and preach to gentles, and he’s clearly reinventing what Jesus was, as he hones his message while preaching around the Greco-Roman world. So the idea that Paul took liberties isn’t in historical dispute, and of course it’s not disputed that he never met Jesus. He learned about Jesus second-hand (at best) from Jesus’s followers (whom he had persecuted), and then he took liberties with the story.

Incidentally, this isn’t a problem for plenty of believers who accept history. They usually just believe that Paul’s epiphany was indeed from God, and God (or the Holy Spirit) steered what Paul said while preaching. Therefore, it isn’t a problem that he diverged from those who actually knew Jesus — those people must be wrong. From a purely historical view, this isn’t a very reasonable scenario, but it’s not a view that’s inconsistent with history. Others would say that it doesn’t matter what Paul said, in the same way that missionaries often altered aspects of Christianity in order to preach it to different cultures around the world. A lot of Christians justify this by saying that one approaches people where they’re at. It’s a kind of royal lie, or way of justifying changing some things around the edges. Of course, this gets believers into the problem of whether the Bible is literally true, but that’s an untenable belief anyway, given easily identifiable contradictions (e.g. two conflicting genealogies of Jesus). The truth is that, despite the constant focus on Biblical accuracy and literalism, most Christians today just aren’t super concerned with the accuracy of everything the Bible; for them, the faith is a living thing, and if they do good and believe Jesus is the Son of God, they’re doing okay. That’s actually a pretty good solution, because it focuses on the Christ of Faith and isn’t so concerned with the historical Jesus. My point is that what I’m saying isn’t incompatible with Christian belief, and there are plenty of educated Christians who accept these things and go right on believing without trouble. And for the record, that’s fine with me.

Returning to the idea that someone who had known Jesus, as Lazarus does in my story, would see discrepancies between what Paul is preaching and the Jesus he knew? That’s pretty indisputable. The people who had actually known Jesus made this same objection, after all.

However, the specific language Lazarus — which is a little strong, but certainly in line with what’s historically responsible — has to do with the larger themes of the story. First, I think it works better dramatically for Lazarus to basically not recognize whom Paul is talking about. There’s this weird disconnect there, this way in which Lazarus is alien to his own experience, that ties into this continuing theme of otherness. The words you quoted refer to how people and events get appropriated and distorted over time, so that our understanding of them shifts. That’s how history works, and Lazarus is seeing it happen in real time, because he’s immortal. That fascinates me. There are those lines in there about how he hopes to see the patterns and shape of history, and it all ties back to Greek drama and the idea of fate. Of course, what he’s watching isn’t the unintended consequences of divine intervention — it’s the unintended consequences of Martian intervention. This idea of unintended consequences, rippling through history, quote fascinates me. We’re seeing the unintended consequences of the Martian who was Jesus, but we’re also witnessing another event — Paul’s visit to Athens — which will have unintended consequences (as the title and the story’s ending suggests).

And of course, Lazarus has changed too. He’s a rural Jew who was raised from the dead, is immortal, and has grown greatly from his time in multicultural, polytheistic, philosophical Athens.

So Lazarus isn’t parroting my thoughts. I can’t separate my own studies of history and fascination with how it works, but Lazarus’s Jesus isn’t my Jesus, and what he’s saying there is more determined by history and the needs of the story.

As for whether Lazarus represents me, I don’t know. There’s something of me in everything I write. I don’t know how it could be otherwise. I do think that, when I was young, I was possessed by magical thinking. I think it’s innate to our brains, and I wasn’t effectively inoculated against it. I wasn’t raised religiously, but I was kind of raised culturally Protestant. My parents rarely took us to a church, and what they told my brother and me about God was sporadic and contradictory. Still, I was interested in the paranormal and alien visitations. I was a believer in that kind of stuff. I guess I believed there were souls. But these were all vague beliefs and research interests. My senior research paper in high school was on Lucifer and the war in heaven. My undergraduate honors project was a novel that involved Jesus. My master’s thesis was on Milton. I think by that point, I was drifting away from magical thinking. I had started to realize that these were stories, and it was kind of silly to claim to know what Heaven was like, or to argue about Milton’s depiction of gunpowder used during in the war in Heaven (which of course had nothing to do with the fall of Satan, from a Biblical point of view — it’s retcons all the way down). In the later half of my 20s, my brain was working in overdrive, and I suddenly felt like all these things that had been mysterious to me — including social and romantic human behavior — were actually not that complex. I could feel moments in which I would have thought magically in the past, or been superstitious, and I felt ashamed at how much time I’d wasted with that kind of thinking, despite my intelligence. Especially in my early 20s, I was very solipsistic, and I spent a lot of time preoccupied with extreme relativism. In my later 20s, I realized this wasn’t very productive, and the world around me might not be “real,” but it’s certainly the closest thing to “real” that we have. It has reliable rules, and it might not be meaningful, but it’s all we can be sure we have. It was a tough transition, but soon my world became a lot simpler, my thinking a lot crisper, and my life a lot happier and more productive.

As for whether Lazarus represents me, I don’t know. There’s something of me in everything I write. I don’t know how it could be otherwise. I do think that, when I was young, I was possessed by magical thinking. I think it’s innate to our brains, and I wasn’t effectively inoculated against it. I wasn’t raised religiously, but I was kind of raised culturally Protestant. My parents rarely took us to a church, and what they told my brother and me about God was sporadic and contradictory. Still, I was interested in the paranormal and alien visitations. I was a believer in that kind of stuff. I guess I believed there were souls. But these were all vague beliefs and research interests. My senior research paper in high school was on Lucifer and the war in heaven. My undergraduate honors project was a novel that involved Jesus. My master’s thesis was on Milton. I think by that point, I was drifting away from magical thinking. I had started to realize that these were stories, and it was kind of silly to claim to know what Heaven was like, or to argue about Milton’s depiction of gunpowder used during in the war in Heaven (which of course had nothing to do with the fall of Satan, from a Biblical point of view — it’s retcons all the way down). In the later half of my 20s, my brain was working in overdrive, and I suddenly felt like all these things that had been mysterious to me — including social and romantic human behavior — were actually not that complex. I could feel moments in which I would have thought magically in the past, or been superstitious, and I felt ashamed at how much time I’d wasted with that kind of thinking, despite my intelligence. Especially in my early 20s, I was very solipsistic, and I spent a lot of time preoccupied with extreme relativism. In my later 20s, I realized this wasn’t very productive, and the world around me might not be “real,” but it’s certainly the closest thing to “real” that we have. It has reliable rules, and it might not be meaningful, but it’s all we can be sure we have. It was a tough transition, but soon my world became a lot simpler, my thinking a lot crisper, and my life a lot happier and more productive.

Let me try to express this another way. Before this shift, I thought the famous Shakespeare quote — “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy” — was a legitimate, meaningful point. It’s a wide world, and who knows what’s out there? Ghosts? Aliens? Gods? Ancient technologically sophisticated civilizations? I would have said there was some evidence for all of this. After this big shift in me, I realized that Shakespeare quote was bullshit. It’s a way to justify including the fantastic in an otherwise realistic play. It’s basically the equivalent of someone in the movie Thor quoting Arthur C. Clarke to justify super dumb shit, which is how that Clarke quote about sophisticated technology being indistinguishable from magic is almost always used. (Also, in that Shakespeare quote, Hamlet’s just seen a ghost with his own eyes, so the quote is at least evidence-based. It’s saying there’s a lot we don’t know, but at least Hamlet is modifying his stance based on having literally just interacted with a conscious, talking ghost.) That quote isn’t a justification to believe whatever bullshit you want to believe, which is how people cite that quote. It’s like saying you believe deer are gods actively creating our universe, and then adding when challenged that “hey, all truth is relative.” Well, yes, but that doesn’t mean anything goes. Relativity doesn’t mean that. There’s no evidence acupuncture or homeopathy or faith healing works, but their believers will say there is, and who are you to say otherwise? When they’re logically completely defeated, out comes that Shakespeare quote.

After this big shift in me, it was like the scales had fallen from my eyes (to coin a phrase). Occam’s razor suddenly clicked for me. I’ve experienced things moving without explanation, sometimes repeatedly, but that doesn’t prove psychic energy or dead human spirits are involved. It’s certainly not the simplest explanation, and no one sits around and talks to ghosts. I can’t dismiss every account of miracles, but we know humans hallucinate pretty regularly and misremember terribly. Also, even the existence of a miracle wouldn’t prove it was caused by a specific god, let alone that the reported details of this god were true, let alone that the afterlife and creation myth that are tied to this god are also true. None of that follows. I believe extraterrestrial life exists, based on the data and how science has constantly shifted us away from the belief that we’re special or the center of the universe, but I don’t believe aliens have visited us. As a logical person, I’m willing to concede it’s possible, and I’ll revise my belief according to the evidence. I personally think it’s more likely that we’re living in some bizarre virtual reality than that any of the traditional religions are true, but I don’t believe either. I’ve since realized that I’m an atheist — meaning a non-theist (I don’t believe in gods). I can’t say I’m never superstitious, or that my thinking is 100% clear. Our brains are so wired to see cause and effect that aren’t there — I prayed, and the rain came, so I assume a connection (which presumes no one else was praying for a clear day and God had moved the clouds into position in advance). But it’s a wonderful relief to realize the weather just has nothing to do with you. In fact, that person who was mean to you probably doesn’t have anything to do with you either. So I’m a lot happier and more productive now. And I think I’m actually more moral too, because I’m focused on people here and now, and I’m able to more calmly and even coldly assess what messages my behavior is sending. This even informs my teaching, where my approach is very focused on demystifying and presenting information in easily understood forms.

It’s this process that makes me identify with Lazarus, in this story. In some ways, he’s a hick from the sticks who’s come to the big city. It’s an old story. But in a more meaningful sense, he’s made a mental journey away from magical thinking. Before his death, he was probably as concerned with Jewish prophecy, arguments over what the messiah meant, and how the world was going to end. Now, he’s been exposed to religions and cultures from a huge area, and he’s picked up a bit of logic. He’s learned to write. And he’s able to look back on this more limited, earlier self, in the story. I’ve changed a lot over the course of my life — and I reserve the right to change again! — so this is something that I identify with. And I don’t think it’s something we often see in fiction.

(more to come in Part III)