[The following post was written by Ron Edwards for his site Comics Madness and is republished here with permission. The entirety of the reader Comments that followed his writing are also included as of 9/16/2016; they have not been edited for content, and they reflect solely the views of their writers.]

Happy birthday to me! I grant you this is an odd topic for my birthday post, as I have zero affinity or resonance with evangelical Christianity. Its impact is definite at second-hand, though, as I think about the number of friends and family who became Jesus People (the early term) and (as soon called) Saved or Born Again during my pre-teens and teens, say from 1974 through the early 1980s. My previous column sort of got me going on the religion/comics topic and it turned out to be autobiographically non-trivial, so here we go.

Happy birthday to me! I grant you this is an odd topic for my birthday post, as I have zero affinity or resonance with evangelical Christianity. Its impact is definite at second-hand, though, as I think about the number of friends and family who became Jesus People (the early term) and (as soon called) Saved or Born Again during my pre-teens and teens, say from 1974 through the early 1980s. My previous column sort of got me going on the religion/comics topic and it turned out to be autobiographically non-trivial, so here we go.

I invite you to contrast this topic with its contemporary, which I wrote about very nearly a year ago exactly, in Superstar. Specifically, the 1960s-70s grassroots tug-of-war over Jesus, which was resolved so thoroughly that the losing side has been scrubbed from memory. Here’s the thing: the winner of that fight isn’t fringe. We are talking about whether Jesus, specifically the personal-ecstatic, you-choose religious identification, is on the side of the Establishment or not. Because when I talk about the “winner,” I mean whether becoming a Jesus person puts you on the right side or the wrong side of temporal authority and general socio-professional expectations. To put it a little differently, does Jesus drop acid or bombs? In terms of personal life-choices, does he hang out with prostitutes or does he stop (“save”) them from being prostitutes?

You’d think that’d be a no-brainer. The various contributions compiled as the New Testament, specifically the Gospels, are non-controversially separable into Jesus (Yeshu, ישוע) stuff vs. Christ (messiah, Χριστός) stuff, which are mashed together mainly via arrangement in a certain order which hides their dates of authorship and their regions of origin. Looking at the textual Jesus, you see at best a street-teacher whacked out on “peace, man,” prone to aggravating/teasing critical-thinking instruction (specifically the Cynic school, κυνισμός), not overly concerned with ordinary social decency, and not lacking an Abbie Hoffman gleam in his eye. Even if he isn’t quite aligned with the bomb-throwing foes-of-society of the story, they think he is, and the authorities are inclined to agree; nor is he above his own acts of what today is called “domestic economic terrorism.” When you consider – for my culture, 1960s-70s Left Coast – the prevalence of Encounter, drugs, mysticism, and social dissatisfaction (see Buddha on the road, Steve! Get’im!), it’s pretty much a perfect fit. Especially if you put aside the grinning stoner smear that kicked in during the 80s and think historically instead of memetically; for a very short bit there, the term “Jesus freak” overlapped with “freak flag.” But that’s not what happened, because text is not what we are talking about, and never were.

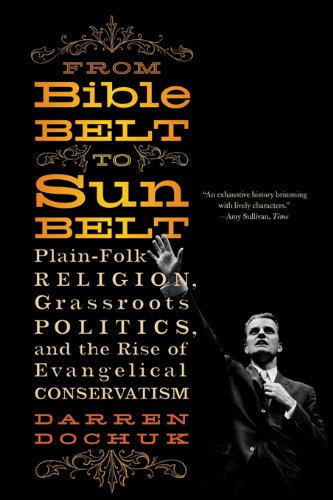

Nor even are we really talking about Christianity, but about America. And America had become the national religion during the 19-teens. The question wasn’t about whether Americans were going to become Christians, but about whether being assertively Christian, as a political identity, would be faithfully American enough. In this, evangelical Christians of Greater Appalachia trod the same twentieth-century path as several other marginal groups: first a dismissed and politically unsuccessful fringe, next combining public unpopular extremism with insider-effort that adopts extreme patriotism; and finally allying with and partly subverting one of the two political parties, and being subverted by it in turn.

This is a very important history! Pretty much exactly a century ago, the term “Fundamentalist” was coined very much in defiance of being mainstream American, including rural economic reform, anti-evolution, and anti-war activism during WWI. Whereas by the 1950s, they were trying to become as American as possible, supporting Cold War militarism with the most extreme possible anti-communism, with their economics reduced to relatively crude positions like blanket anti-taxation. This phase, the openly John Bircher Society one, is associated primarily with resistance to civil rights in the South, but while all eyes looked in that direction, something more powerful was happening in Southern Cal, in the exurbs where hundreds of thousands of Greater Appalachians had emigrated to work for Boeing, and more importantly, to organize a new kind of church that used TV to rake in money, and the money to found colleges and think tanks. By the mid-late 1970s, and given the body blows to the Republican power structure following Nixon’s political demise and Rocky’s interesting literal demise, this effort focused hard on homosexuality and abortion, and succeeded dramatically and, to everyone else, entirely unexpectedly, partly through infiltration and partly by riding on mainstream fear of rapid social change.

This is a very important history! Pretty much exactly a century ago, the term “Fundamentalist” was coined very much in defiance of being mainstream American, including rural economic reform, anti-evolution, and anti-war activism during WWI. Whereas by the 1950s, they were trying to become as American as possible, supporting Cold War militarism with the most extreme possible anti-communism, with their economics reduced to relatively crude positions like blanket anti-taxation. This phase, the openly John Bircher Society one, is associated primarily with resistance to civil rights in the South, but while all eyes looked in that direction, something more powerful was happening in Southern Cal, in the exurbs where hundreds of thousands of Greater Appalachians had emigrated to work for Boeing, and more importantly, to organize a new kind of church that used TV to rake in money, and the money to found colleges and think tanks. By the mid-late 1970s, and given the body blows to the Republican power structure following Nixon’s political demise and Rocky’s interesting literal demise, this effort focused hard on homosexuality and abortion, and succeeded dramatically and, to everyone else, entirely unexpectedly, partly through infiltration and partly by riding on mainstream fear of rapid social change.

This is when, after a century of effort, the “Saved” version of Jesus and its political associations shifted from a birth-culture, imposed, instructed phenomenon into a grassroots, spreading phenomenon – specifically, from the exurban displaced Appalachians in Southern Cal straight north up the west coast for all and sundry. A bit part of that latter step meant wresting Jesus away from his flirtation, in that very region, with Beatniks, SDS, anti-war, Unitarians, civil rights, counter-culture, “eastern” philosophy (however muddled), and unkempt habits. All that stuff had to be re-labeled secular humanism (an older, not particularly applicable term) and flatly immoral (which would have surprised Alexandre Comte, its author, a bit of a smug scold himself) … and it worked.

Pop/mass culture matters a lot here. The Saved Jesus had no choice but to keep the long hair and rock-and-roll/folk, with some effort to revise them into suitably on-message and disinfected form. Informal, viral access was crucial – TV was certainly the primary player, but radio is surprisingly more effective, and stations immediately started blasting from just south of the Mexican border, safe from the FCC. And as a little fillip to it all, along came the comics. There are three from this period (mid-70s) that I deem to be directly influential, if not on me, then on the immediate culture, and certainly prevalent in my experience at the time and certainly influential on many people I knew well. It is, indeed, why the parents of my pal Robbie threw away all his comics, except for Archie, thus why Robbie took to reading Conan the Barbarian at my house.

One branch of the comics effort, perhaps the most lasting and well-known, was Chick Publications, by Jack T. Chick, which published the well-known tracts and a line of full-size titles too. Even then, they were well behind the times, adhering to a long-failed version of Creationism, so-called “Scientific” Creationism, rather than the glossy Intelligent Design then in development at the Discovery Institute. But putting aside my specific interests in Big Daddy? and Dark Dungeons as an evolutionary biologist and role-playing game publisher, and speaking more generally, I suspect the entire effort was retrograde to a self-defeating degree. There was no “brave new America!” in them – to be a Chick believer, that is, to agree with his message, you branded yourself an outcast, tacitly the target for the next crucifixion, because you defied the Man so thoroughly, especially in his most vile manifestation of the university professor. The message was consistently as anti-middle-class as much as it was anti-intellectual, and since it was also opposed to radicalism, the question is thus unintentionally posed for the reader, of what the newly-cleansed and minted Christian young person is supposed to do, now that he or she obviously can’t participate in most social activities, earn a degree, or even find any sort of job. I’d like to know more about Chick Publications’ social impact along its intended lines, as I suspect it has been minimal, such that a Jack Chick “fan” is actually a bemused collector rather than a religious adherent. (I don’t claim to be a scholar of each and every title’s exact message – if anyone knows more about this than me, please speak up.)

One branch of the comics effort, perhaps the most lasting and well-known, was Chick Publications, by Jack T. Chick, which published the well-known tracts and a line of full-size titles too. Even then, they were well behind the times, adhering to a long-failed version of Creationism, so-called “Scientific” Creationism, rather than the glossy Intelligent Design then in development at the Discovery Institute. But putting aside my specific interests in Big Daddy? and Dark Dungeons as an evolutionary biologist and role-playing game publisher, and speaking more generally, I suspect the entire effort was retrograde to a self-defeating degree. There was no “brave new America!” in them – to be a Chick believer, that is, to agree with his message, you branded yourself an outcast, tacitly the target for the next crucifixion, because you defied the Man so thoroughly, especially in his most vile manifestation of the university professor. The message was consistently as anti-middle-class as much as it was anti-intellectual, and since it was also opposed to radicalism, the question is thus unintentionally posed for the reader, of what the newly-cleansed and minted Christian young person is supposed to do, now that he or she obviously can’t participate in most social activities, earn a degree, or even find any sort of job. I’d like to know more about Chick Publications’ social impact along its intended lines, as I suspect it has been minimal, such that a Jack Chick “fan” is actually a bemused collector rather than a religious adherent. (I don’t claim to be a scholar of each and every title’s exact message – if anyone knows more about this than me, please speak up.)

There’s a smoother but nevertheless still-uneasy balance between fringe and mainstream in the Christian Archie comics, which I didn’t know much about. They weren’t actually published by Archie Comics (the company) at all, but by Spire Christian Comics. Spire oddly had permission to use the Archie characters throughout the 1970s, via the Archie Comics writer-artist Al Hartley. I’d like to know more about that because the available narrative seems to lack a certain categorical solidity … comics publishing companies do not, as a rule, turn over their major characters to a work-for-hire scribbler at another entire company just because he feels like making extreme socio-political statements with them.

You may laugh, but this reader actually avoided anything Archie with some care, as I had first encountered the characters in the infamous “Nightmare Nursery” in the 1972 Life with Archie (I was EIGHT; read it here), and decided to stay with safer fare like Eerie and Creepy. Anyway, learning about the Spire series’ run has finally made sense of why, during the late 70s, my friends’ newly-Saved parents would only let them read Archie, which to my eyes, still bleeding from that (Good Lord! <choke>) fucking demon teddy-bear story, seemed sort of odd. What’s in the Spire Archie, and what do they say?

Stick with me, it’s a precision-strike concept: the perception that society is Recently Messed Up and Gone Wrong, plus the belief that if we can only listen to the Word, a decent society is “around here somewhere,” or “just past, still recoverable.” Said society being identical to Riverdale, or at least an uncritical reading thereof. You get the idea that if you got with Jesus, and if everyone would, then we’d be in a soft-focus version of the earlier Archie days, a halcyon small-town time of fun, hi-jinks, and cleanly romance … in which not only drugs and awful unhappy nonwhite people are absent, but especially criticizing American military policy is notably absent. See the difference? You don’t get with Jesus as an alternative because all America is bad, but because Jesus gives you access to the “real” America, definitely not fringe, even helping you build or heal or recover it. Scratch that gently-smiling Archie with the weird over-sized pupils, and you find a Bircher … just as that organization, serial numbers scrubbed off, provided the weight for the Christian Right to rebrand itself as Reagan Republicans, after failing to do so with Goldwater in 1964.

Stick with me, it’s a precision-strike concept: the perception that society is Recently Messed Up and Gone Wrong, plus the belief that if we can only listen to the Word, a decent society is “around here somewhere,” or “just past, still recoverable.” Said society being identical to Riverdale, or at least an uncritical reading thereof. You get the idea that if you got with Jesus, and if everyone would, then we’d be in a soft-focus version of the earlier Archie days, a halcyon small-town time of fun, hi-jinks, and cleanly romance … in which not only drugs and awful unhappy nonwhite people are absent, but especially criticizing American military policy is notably absent. See the difference? You don’t get with Jesus as an alternative because all America is bad, but because Jesus gives you access to the “real” America, definitely not fringe, even helping you build or heal or recover it. Scratch that gently-smiling Archie with the weird over-sized pupils, and you find a Bircher … just as that organization, serial numbers scrubbed off, provided the weight for the Christian Right to rebrand itself as Reagan Republicans, after failing to do so with Goldwater in 1964.

I got a bit out of chronology there, because Spire Christian Comics actually got its start with its adaptation of The Cross and the Switchblade in 1972. Contextual knowledge first: David Wilkerson’s extremely-successful book of that title was published in 1962, then the movie starring Pat Boone and Erik Estrada appeared in 1970, and finally the comic by Hartley came along in 1972, in which the characters strongly resemble the aforementioned actors but with a slimmed-down plot.

I got a bit out of chronology there, because Spire Christian Comics actually got its start with its adaptation of The Cross and the Switchblade in 1972. Contextual knowledge first: David Wilkerson’s extremely-successful book of that title was published in 1962, then the movie starring Pat Boone and Erik Estrada appeared in 1970, and finally the comic by Hartley came along in 1972, in which the characters strongly resemble the aforementioned actors but with a slimmed-down plot.

The comic – just a single issue – went through two phases of long-running, repeated-print publishing: the first with Spire, itself owned by Fleming H. Revell, and then from 1981 through 1988 via Hugh Revell Barbour, who has played no small role in mass-market Christian Right publishing. Learning about those dates and the high-volume print runs was a bit of a relief, because, I swear, during any time I’ve been actively seeking comics, the damn thing was everywhere! I’d be in someone’s house at age 10, and there it’d be. I’d rifle through a stack of comics at the weird guy’s little nook bookstore in New Monterey, and there it’d be. And a decade and a half later, grown up, I’d be staying at a friend’s parents’ house during an Arizona hitching-and-hiking trip, very much Born-Again middle-classers in Tempe, and among the kibble in the guest room I stayed in, there it was. Curiosity but mostly desperation, because I’m one of those people who simply has to be reading something, led me to read it multiple times.

At present writing, though, I haven’t seen it for about, gosh, over twenty years. You can read it right here. A couple current impressions: first, I’d completely forgotten that foregrounded woman on the cover, which I otherwise recalled in detail. She doesn’t fit in even a bit, completely off-style and distracting from the action. Second, I’d swear that little black kid was in The Cosby Kids. Even without taking these and other opportunities for snarking, the story itself is terrible, unconvincing … yet there’s one bit of grit in there, which is also the only bit from the inside pages that I’d consistently held in memory.

It stands out. The rest is completely banal, even laughable, but these two panels were and are uniquely harsh: “spics” and “nigger,” obviously, unlike the unconvincing Hollywood-gang speak used in most of the story; the bullet scar, which although just a scribble made me shudder a little as a kid, as comics of the day showed no clinical effects of violence; and far more humanity for these particular black characters than the hackneyed depictions of the rest. I haven’t seen the film but am curious as to whether the latter image is adapted from it directly; it looks as if it could be. As an aside, I wonder how that all-gangs-gather scene in the film compares to the “Can you dig it” sequence in Warriors …?

For a flickering-flash second, the text acknowledges that there is in fact a voice out there, for a moment hearing it without labeling it Other. And not in a way easily dismissed as “well they can’t help it, they were brought up amidst prostitutes and heroin,” either. It doesn’t give the overall story any weight, but it briefly has weight. I wouldn’t be surprised if this long-running, well-known single-issue story did have some impact on that basis alone.

My final point: why not more? I can think of two ways that I might have expected to see a lot more visible religion in U.S. comics, specifically evangelical or at least grassroots Christianity. First, why not lots more companies like Spire, with wide range of titles in ordinary distribution (in the 70s, on the spinning racks; after that, in retail)? It’s an obvious market with massive promotional and viral potential, and it’s not like that particular subculture had any problem spotting such opportunities. Second, to turn to Marvel and DC, one of the core factors in their content – at least at times – is seeing the details of authentic modern life, and casual religious identity is a big part of real life. So I’m interested in when it shows up and when not. I’ll get a post going about that.

Quick history help requests: One sentence in Wikipedia, as of this writing, claims Spire Christian Publications was a subset of Fawcett Comics, but I can’t confirm that through any other reference – rather to the contrary, concerning the history of Barbour & Company. Anyone? Also, how on Earth has Chick Publications been funded and distributed – especially back in the 1970s and 80s?

Here’s, maybe, a clue on how Chick comics were distributed. The first one I ever saw, one about evolution, I picked up in a parking lot in St. Louis, Missouri circa 1976. There seemed to be a number of them left around. My dad didn’t see me pick it up. I read it in the car. It freaked me out a good deal. Not the subject itself, but the contentiousness. Adults hating on adults about stuff I didn’t really understand. I was down with evolution and accepted science was never controversial or threatening in our house. But it was beardy-weirdy professors getting screamed at — or doing the screaming. I don’t quite remember. Anyway, I threw it in my toy box where it would resurface from time to time. I’d read it and it would give me a queasy David and Goliath vibe, helped no doubt that it smelled like asphalt still.

I remembered finding this comic years later, in 1983, when the KKK did a propaganda dump in my high school, looking for new members. That was how they rolled–straight up PSYOPs. Drop leaflets and let the circulate. The effect was so surreal and gave off such a stink of illegitimacy. But I’ve been a believer in the efficacy of PSYOPs tactics ever since.

By the time I saw the infamous Black Leaf comic in 1984 my sense of irony was sufficiently developed that I joined in heaping scorn and derision on its ambitions. I was right in the heart of RPGdom, right in the heart of the bible belt. Yeah, it was a huge deal for the Christian families, to an extent that is difficult to express today with any credibility. Thing is, I _immediately_ understood this was another volume from the Chick library, so strong was the branding of the original comic. Chick, like the KKK, had staked out a malevolent territory in my imagination where their adherents were numerous and organized, if not quite visible.

That was definitely Big Daddy; your description is unmistakable.

What interests me is that such operations, i.e., mass leafleting, is labor-intensive – people have to box those things, ship them, drive them around, drop them, et cetera. With that kind of distribution effort on tap, it surprises me that there weren’t, say, ten or dozens of Jack Chicks all over the country, pumping out a wider variety of titles. Especially since, as I said, Chick’s content was high on energy but low on convincing content. I’ve had many, many students from evangelical backgrounds in my college classrooms – remember, evolutionary biologist here – and speaking specifically of those who retained and respected their religious outlook, their view toward that kind of material was one of universal embarrassment.

Putting aside my dislike of his views, I must acknowledge that Chick was and is a totally classic American underground comix creator. You could put his work in a row with Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, and really, anyone you could find through the whole course of the cartoonists featured in, say, the Chicago Reader or the Village Voice, and content aside, he would fit right in stylistically and in the general “goddammit I’m drawin’ it” way that defines indie/auteur cred among those who categorize that way.

That’s the thing about voice and line, the main signifiers in writing and depiction. They are always characters, voices in their own. I the same way I can still identify my best friend’s handwriting just by his line, a strong artist can access your head in an instant with a huge ensemble of meaning. I think lack of voice, or a babble of inchoate ones, is why people generally find the internet initially so welcoming. “Goddammit I’m drawin’ it,” is exactly the case here.

Chick’s stuff was getting to Australia in the 1970s. Probably through evangelical type networks, which have always existed here.

In Australia, by the late 70s/early 80s and to the present, anti-establishment, left-wing Christianity was a predominantly Catholic phenomenon. There were historical roots for this in the tensions between “Irishness” and British Empire loyalism, which was the original version of Australian nationalism.

This included people who identified with Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker Movement, which brings me to the comics relevant point that Dennis O’Neil has mentioned that he was reading Catholic Worker during the period he was writing his (early) Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories.

And Happy Birthday, belatedly.

The Liberation wing of Roman Catholicism is definitely a big deal, and I didn’t know about the Irish-associated aspect of it. My contact with it mostly concerned Central America. Makes me want to write a retro “in the 80s” story about competing supers in the corridors of Catholic power. Shoot – even set most of it in the Vatican, that’d be cool.

It’s interesting that as mainstream American culture became increasingly evangelicalized, the entertainment industry, including comics, resolutely resisted it. They didn’t resist all kinds of conservatism, political and social, but evangelical culture was not explicitly present in films, in TV, in comics, in music, and meanwhile a walled garden of Christian Rock, Christian Romance Novels, Christian Children’s TV, and so on sprang up.

This is why Evangelical Christians could feel like a persecuted minority in a culture they increasingly controlled: they didn’t see themselves in Hollywood; they had to make their own specially-baptized consumable culture. And they did! And it was huge and influential! But it was secondary to the “real” entertainment industry.

And while they resented it they kind of needed it because if you take Evangelical Christianity out of its self-imposed ghetto and put it on the big screen, you’ve got to make a decision as to whether (as a creator) you are going to submit to it uncritically or submit it to criticism. It brooks no compromise, it allows no multiple-perspectives. So you *can’t* put Evangelical Christianity on the screen, because you would be excoriated for it unless you did it exactly the way the Evangelical Christians want you to.

They don’t resent not being shown on the screen, they resent not owning the screen.

But not owning the screen is understood as proof they are a persecuted minority.

Source: seeing this from the inside, or at least partially-inside, growing up, of course. (Not as “inside” as some people — West Michigan was religiously conservative but it was not the same *kind* of religiously conservative as the Bible Belt, so this Evangelical perspective was mixed with other perspectives.)

Yes. The book for you is The Battle for God, by Karen Armstrong. Also, although I keep talking about Greater Appalachia, that region has always contributed waves of migration to other areas, usually operating as an influential if lower-status subculture. Lots of cops, prison guards, low-skill high-hours factory work.

Liked by 1 person

When I think back on my 60’s-70’s in the intersection of New Netherlands & Yankeedom, it feels a bit different. Maybe – a persistence of “Pete Seeger” Christianity? Perhaps the rock-and-roll, long-haired Saved Jesus folks persisted/survived (as non-mainstream, but not ENTIRELY enemies to America) further into the coming Fundamentalism? I remember a hymnal (not really labeled that, or used EXACTLY like that, but pretty close) with Seeger, Dylan & Joni Mitchell right alongside non-adapted Christian hymns.

Which probably influences my thoughts on “Why not more?” re: comics. I knew a guy who changed from good-old Rock and Roll musician into Christian Music Guy, and there was great confidence that his younger listeners would stay within the Christian Music genre. Could the fear of Christian comics as “gateway drug” (yeeks, is that concept ever anything but a fear/tool?) to the other mind-corrupting, bad-art-value, “un-American” comics have been too strong? Now that the comics-ish Marvel Cinematic Universe and etc. is Big, maybe we’ll start to see the growth of Christian Comics, maybe as an (attempted, anyway) walled garden like Ed mentions?

I would really like to know whether Spire-style Christian comics were as rare as they were because mainstream distribution and other dynamics kept them out, or because some component or undercurrent within evangelical culture didn’t want to get in.

Me too – a short bit searching the internet for help found only a few websites about Christian comics. I saw some people saying things like (my paraphrase) “our Christian testimony is more important than our comics,” which maybe is an aspect of evangelical culture that’s a barrier to them getting in … but pure speculation as to how to weigh that (and other within-evangelism stuff) vs. outside forces.

Oh wow, look at this: Why Jesus and comics need each other. Bit of a jaw-dropper.