(The following article by Fredrik Strömberg was originally posted on the Mizan Project website. It is copied here with permission.)

Superheroes from the Middle East: Adaptation of the Genre?

This is the third essay published here on Mizan Pop in our Muslim Superheroes series. The first and second installments in the series can be read here and here.

America has been exporting superhero comics for more than seven decades; nevertheless, there have been few commercially successful comics created in that genre in the rest of the world. Given that there have been several violent conflicts between the United States and Arab or Muslim-majority nations over the last few decades, it is intriguing that attempts at establishing a line of original superhero comics were made in the Middle East in the first decade of the twenty-first century by two different publishing houses: AK Comics in Egypt and Teshkeel Media Group in Kuwait.

But what are superheroes, really? My definition of the superhero genre would include the following conventions: superhuman abilities, for heroes and villains; a strong personal moral code as a driving force for the heroes; an origin story that explains the abilities and the moral code; a clear visual branding of each hero, mainly through costume design; a mundane secret identity that contrasts with the superhuman identity; recurring, violent clashes between heroes and villains; a sexualization of the heroes, mostly seen through the male gaze; and finally a cohesive and contemporary, although alternative, version of the reader’s world.

American superhero comics have been exported to the Middle East since the 1960s, starting with Superman. There have also been superheroes created in the Middle East before the advent of AK Comics and Teshkeel, but mostly in the form of parody, as in the Algerian Maachou, the Algerian Superman (1983) by Menouar Merabtene or Super Dabza (1986) by Abd al-Karīm Qādirī.1

In light of the above, AK Comics was an anomaly when founded in 2001 or 2002 (different years are cited in different sources) by Egyptian businessman Dr. Ayman Kandeel (whose initials gave the publishing house its name), with the aim of producing superhero comics that would promote peace and understanding in the Middle East.2 AK Comics started publishing in 2003–2004, with four different titles collectively called Middle East Heroes: Zein, Aya, Jalila, and Rakan.

The titles were all set in the same alternate version of the Middle East. Zein dealt with a time-travelling descendant of an old family of pharaohs, whose origin story is similar to that of Superman. Aya is a crime-fighting superhero endowed with an origin story and attributes similar to Batman. Jalila is a nuclear scientist who gains her powers in a nuclear blast, which mirrors the origin story of the Hulk. And finally, Rakan, which is not really a superhero comic, was set in the distant past, featuring a sword-wielding barbarian who seems to have been inspired by Conan the Barbarian.

Kandeel, as founder, seems only to have been involved in the production of the initial comics. After this, writing was left mostly to lesser-known U.S. scriptwriters and the art chores to studios based in South America, involving American comics veteran Daerick Gröss only at the end of the run. AK Comics were initially distributed in a number of Middle Eastern countries, and the publisher twice attempted to enter the American comics market, in 2003–2004 and in 2005–2006. However, despite respectable but not spectacular sales figures during the second U.S. launch, the fact that the whole enterprise consisted of only about 20 issues in total—with all of the titles both ending in the middle of ongoing stories and including ads for further issues that were never published—indicates that it was not a resounding financial success.3

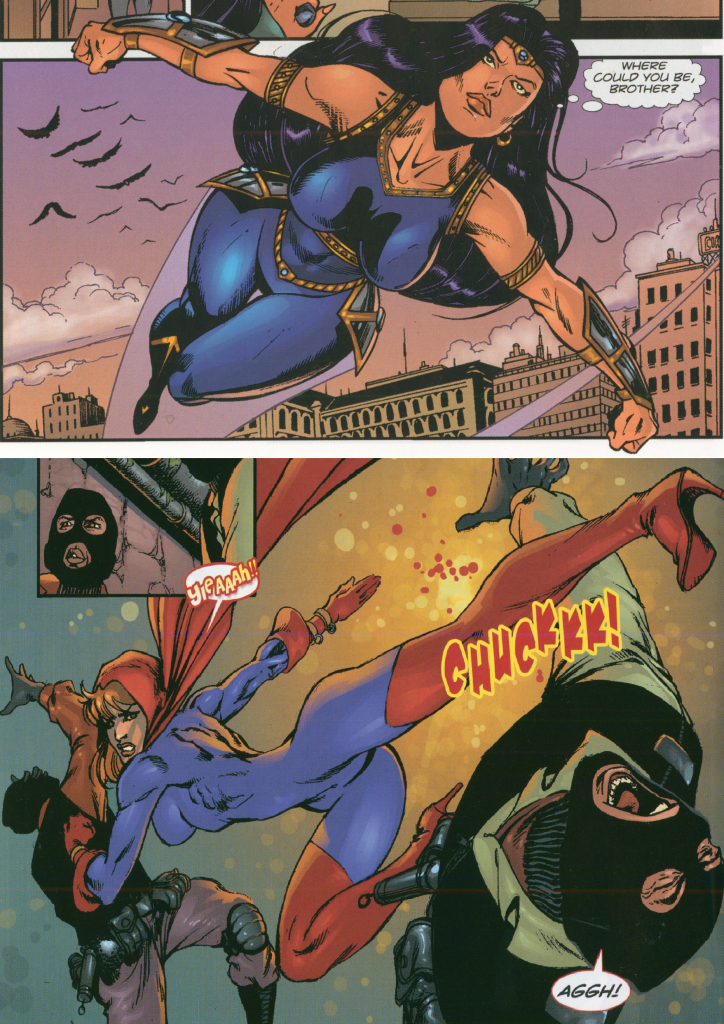

Jalila and Aya, two of the heroines from AK Comics, designed in a fashion similar to many of their American counterparts (© AK Comics 2006).

AK Comics stayed true to all of the conventions of superhero comics noted above. This meant that the only difference between their comics and ones published in the U.S. was that the stories were set in the Middle East. The content only superficially mirrored the Middle Eastern origin, despite the openly stated intent of doing the exact opposite. This resulted in weak copies of the American superhero comics, which did not excite readers in either the Middle East or the U.S.

Teshkeel Media Group was founded in 2004/2005 (again, different years are cited in different sources), initially as a publisher of translated American superhero comics. But already by 2006, Teshkeel’s endeavors were refocused on the publication of its original superhero comic book, The 99. Teshkeel was founded by the psychologist Dr. Naif al-Mutawa, who has gained worldwide attention and acclaim for his efforts to create a cultural bridge between the Middle East and the Western world.4 Al-Mutawa also had a didactic aim with his comics: “Islamic culture and Islamic heritage have a lot to be proud and joyful about.The 99 is about bringing those positive elements into global awareness.”5

The 99 is set in an alternative version of our world, in which the knowledge and power of a fabled library in the Middle East imbues the ninety-nine “Noor Stones” that, upon contact, can turn the right person into a superhero. Dr. Ramzi, a character that shares traits with the group leader Charles Xavier of the X-Men, gathers the people who have found the Noor Stones around him and sets them working for the greater good through his organization, the 99 Steps Foundation.

While al-Mutawa was officially involved as co-writer of almost all of The 99, he also enlisted high profile U.S. scriptwriters like Fabian Nicieza and Stuart Moore, and employed respected American artists such as John McCrea and Ron Wagner. Teshkeel’s comic books seem to have been more successful than those of AK Comics, as the enterprise kept going from 2006 up until September 2013, when publication ceased after a run of over forty separate issues.

Noora, ‘The Light,’ from The 99, with a more modest design compared to many American super heroines (© Teshkeel Media Group 2007).

Teshkeel chose a largely different approach to the superhero genre as compared to AK Comics and, to a greater or lesser degree, they made significant alterations to almost all of the conventions of the genre presented earlier. Eliminating violence and significantly downplaying the sexualization of the heroes were the major adaptations. But other changes were also made, such as the use of superpowers that were designed to fit into a group rather than to work independently, which together with the communal nature of the heroes’ moral code also radically changed the way the stories in The 99 were told, as compared to their American counterparts. The group and their shared goals were always at the forefront in these stories, as opposed to the often much more individualistic approach in American comics, including those that feature groups of superheroes.

This meant that Teshkeel, through adaptation, created something more original than AK Comics. By adapting almost all of the conventions, however, they changed so much that their comics moved closer to the genre of information comics, comics “designed to educate, inform, or teach the reader something.”6 This is consistent with the way comics made in the Middle East are often viewed, as didactic vessels intended to convey information for young readers. However, when moving towards the more educational information genre, The 99 lost some of the appeal of the original genre.

The efforts made by AK Comics and Teshkeel indicate that the conventions of the superhero genre are too immersed in American culture to be directly appropriated into a Middle Eastern setting without adapting them; however, by doing so, a publisher risks straying too far from the genre’s core. This could lead to the creation of a wholly new genre, but this does not seem to have happened yet.

[1] See Allen Douglas and Fedwa Malti-Douglas, Arab Comic Strips: Politics of an Emerging Mass Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 180.

[2] Ed O’Loughlin, “Middle East’s First Superheroes Out to Change Their World,” Sydney Morning Herald, September 24, 2005.

[3] Daniel Williams, “Arab Superheroes Leap Pyramids in a Single Bound,” Washington Post, February 16, 2005.

[4] Al-Mutawa has, among other things, been given the Eliot-Pearson Award for Excellence in Children’s Media from Tufts University, the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations Market Place of Ideas Award, and the Schwab Foundation Social Entrepreneurship Award. He has also been named one of the 500 Most Influential Muslims by the Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Center four years in a row and, in 2013, Gulf Businessincluded him among its “Top 100 Most Powerful Arabs.”

[5] Naif al-Mutawa, “Naif’s Notes,” in The 99 #12 (Teshkeel, 2008).

[6] J. Caldwell, “Information Comics: An Overview,” presented at the Professional Communication Conference (IPCC 2012).