[With the apparent close of the IslamiCommentary site from the Duke University Islamic Studies Center (DISC), Sacred and Sequential is cataloging a number of their articles pertinent to comics and Islam for continued online access. The following, if altered at all, has been edited only minimally for clarity and/or ]

Kismet Seventy Years Later: Recognizing the First Genuine Muslim Superhero

by A. DAVID LEWIS for ISLAMiCommentary on MARCH 20, 2014:

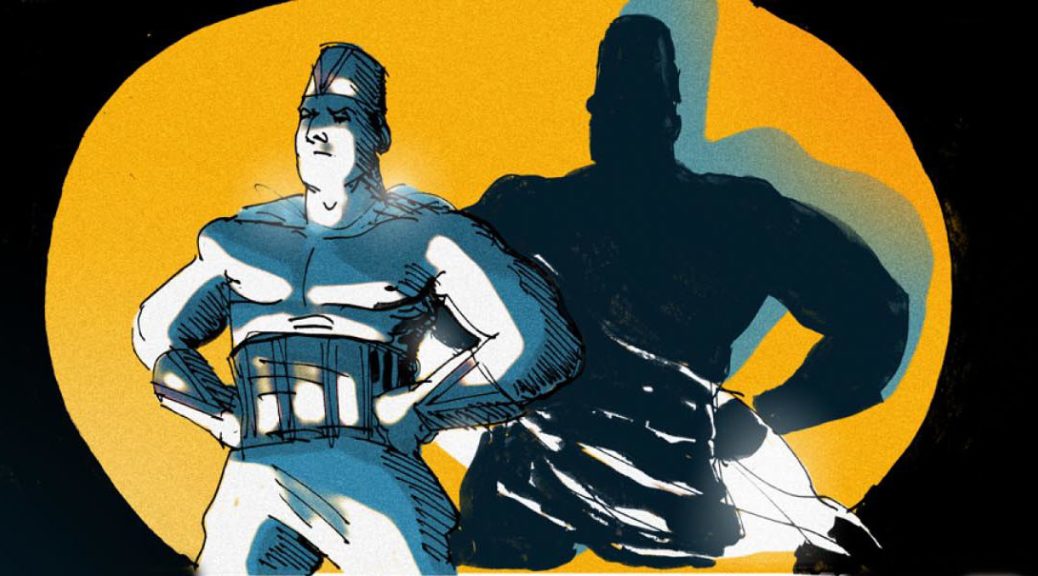

Kismet may not be the first Muslim superhero, but he may be the first worthy of that title. Some buffoonish characters preceded him, and other orientalist caricatures appeared on earlier comics pages, but without either superpowers or other key elements of the genre. This month, on the seventieth anniversary of his first appearance, it’s a fitting time to reintroduce and recognize Kismet, “Man of Fate;” the first genuine Muslim superhero.

The superhero as a genre found its first real traction, famously, in the pages of Action Comics #1; the 1938 debut of Superman. Like Kismet, the character of Superman had his antecedents, prior masked men and super-powered protagonists either on comics pages, on radio, or in print pulp novels. But it wasn’t until Superman crystallized the conventions of a) being driven by a quest for justice and defense of the weak; b) demonstrating abilities beyond that of a normal person; and c) having a costume and secret identity; that the superhero genre became clearly recognized.

1944 — six years after Superman — wave upon wave of superhero characters, with varying success, had been pouring into audience’s hands.

1944 — six years after Superman — wave upon wave of superhero characters, with varying success, had been pouring into audience’s hands.

Some developed their own profitable followings: Batman, Captain America, Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, etc. Others, though, were cheap knock-offs and imitators; copying the generic superhero formula but with little new or novel to add.

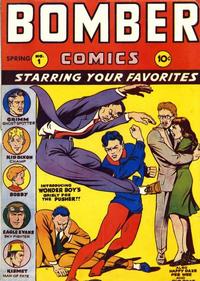

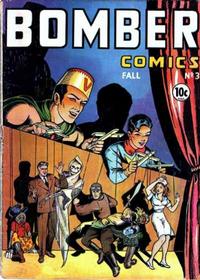

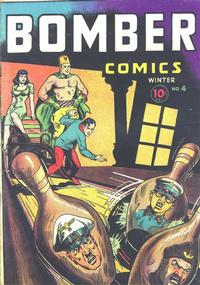

Alongside Kismet in the pages of Bomber Comics were the likes of Dr. Grimm, Ghost Doctor, the meteoric Wonder Boy, and a number of other wartime characters lost to obscurity.

Kismet, however, bears recognizing and reclaiming, not only for the fact of his being Muslim but also for the uncommon subtlety of his character in a time of ham-fisted, gimmick-dependent heroes. Whereas other do-gooders had only a vague or passing rationale for their escapades, Kismet was situated right in the heart of ‘40s Europe, fighting Nazi forces in their many forms. From Southern France, to the Czech Underground, to the German Bavarian Alps, Kismet journeyed to wherever his Mission expressed itself.

He proved himself ready to confront Nazi oppression in whatever shape it took. In one adventure, he thwarts a savage Gestapo revenge scheme, while in other tale he opposes supernatural emissaries from Hades – yes, literally from Hades – in their alliance with Adolph Hitler. The scenarios may have been outlandish but, if nothing else, they displayed the versatility of Kismet as a character and the enormity of his Mission.

m akin to that of Captain America, but also demonstrates being a master of disguise — having the stealthy skills of a ninja or cat burglar, employing the intelligence of a learned tactician, and so forth. But do these argue for his having superpowers, per se, or is he, like Batman or Avengers’ archer Hawkeye, a “normal” man able to triumph in abnormal circumstances?

Comics scholar Jess Nevins looks to Kismet’s alternate title, his being the “Man of Fate,” to explain all of the character’s truly special abilities: “Kismet’s super-power is that he knows what is fated to be, and uses that to his advantage.”

Nevins points out that it is Kismet’s uncanny ability to see ahead and anticipate what punches are coming next and act accordingly that gives him the upper hand when combatting an assailant, rather than the hero’s martial arts skills.

“It has been written that the hand is quicker than the eye!” quips Kismet as he sidesteps the aggressor’s attack and delivers an immediate counter-punch. Notably, the Star Wars prequel The Phantom Menace, explained young Anakin Skywalker’s abilities in roughly the same way; i.e. his ability to glimpse ahead and nearly simultaneously respond to unfolding events is an expression of his potential Jedi power. Here, nearly sixty years earlier, we have a Muslim superhero employing a similar Power on behalf of the wartime Allies.

Beyond his Mission or his Power is Kismet’s peculiar Identity. All of his Bomber Comics appearances are credited to author and illustrator Omar Tahan, of which there is no other publication history. In all likelihood, “Omar Tahan” was a pseudonym for one or more of the creators developing these adventures for Elliott Publishing; working collectively under a pen name was not uncommon during this early era of comic publishing history.

Either the medium was regarded as too trashy for both self-trained and formal artists to attach their names, or these draftsmen were of Jewish background that would have been revealed by their real surnames. (This was an era in American history characterized by anti-Semitism and outright prejudice. Artists needed to hide behind a safe veneer lest they be outright fired and potentially blacklisted.) Whatever the case, “Omar Tahan” was as likely as fictional as “Kismet”; a name that may have lent the character an additional air of authenticity and exoticism in the eyes of the comic’s largely Christian-American readership.

Regardless, the best thing Omar Tahan did – whoever he was/were – was not provide Kismet with a backstory or alter ego. This may seem to argue against the Identity element of superheroes until one considers that the title Kismet and his shirtless costume with cape, gloves, and fez all point to this not being his ‘everyday’ appearance. Kismet could not have been born “Kismet,” nor could his garish costume be his daily wardrobe. Instead, they act as markers for concealing an identity that is never explored – much to one’s relief! In all likelihood, the mind(s) constituting “Omar Tahan” did not have the background or personal knowledge to flesh out a believable, nuanced Muslim character. So, rather than his being burdened with stereotypes and excessive orientalism, Kismet was able to remain an unfettered and attractive character.

So, where is the “Muslim” in this “first genuine Muslim superhero?” There are superficial signs, certainly, such as his prohibition against drinking alcohol (“When the brain is soaked with wine, the fist is not obedient to its master,” he says.) as well as his exclamations of “By the beard of the Prophet!” and “By the star and crescent of Islam!” These smack of ridiculous ‘othering’ to the modern ear, maybe, but they are both in keeping with the hallmark catch-phrases of the superhero genre and are mild when compared to the highly racialized accents and speech patterns common during the era. (He even quotes Jesus, though, as “the tongue of wisdom,” not the Son of God.) Assuming the reader missed the omniscient narrator naming Kismet as a Muslim hero, these sayings by the character helped to signal and reinforce his identity.

What’s most Muslim about Kismet, though, is his admirable purity. He is immediately accepted by the Czech Underground as being an ally to their cause, no questions asked. Likewise, Kismet is well known to the Nazis as a terrifying opponent; even the forces of Hell identify him as being their adversary. In a time where even Batman or Superman let criminals fall to their deaths, Kismet never takes an opponents’ life. The blood is on the hands of the Czech Underground for the assassination of a Nazi official, not Kismet’s for providing a distraction. The death of a Nazi pilot is only Kismet’s responsibility in that he was unable to prevent the plane from being shot down. If he has the ability to see the immediate future, Kismet challenges himself to avoid adding to the body count; to never be the aggressor or an instrument of punishment.

Kismet acknowledges, in all actions, that “it is Allah’s will.” It’s not an excuse or an evasion for Kismet: It’s his faith. Establishing an early baseline for the morality of the superhero, Kismet leaves his enemies’ fates to Allah’s wishes, to Fate itself. And, as such, the character deserves a far better legacy for himself than to be forgotten at the bottom of an old comics bin.

Bomber Comics Cover images can be found at http://www.comics.org/series/17336/covers/. Whole issues are difficult to come by, but can be accessed through the Library of Congress and at Michigan State University (MSU), though not available online through MSU.

[…]

This article was made possible (in part) by the Transcultural Islam Project, an initiative launched in 2011 by the Duke Islamic Studies Center — in partnership with the Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations and the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies — aimed at deepening understanding of Islam and Muslim communities. See www.islamicommentary.org/about and www.tirnscholars.org/about for more information. The Transcultural Islam Project is funded by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author(s).