[The following is a guest column by Matthew William Brake.]

This may be the weirdest Advent post ever.

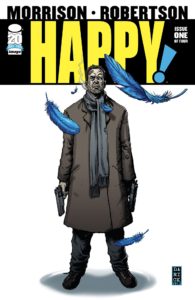

Grant Morrison’s Happy! is an odd little comic (now adapted to a TV series on SyFy) about a former-cop-turned-hitman Nick Sacks who, after a particular hit, finds himself pursued by powerful people believing that he has a password belonging to a deceased (but very rich) don. After the hit at the beginning of the story, he has a heart attack and now finds himself seeing an imaginary blue unicorn named Happy. Happy is the imaginary friend of a young girl named Haley, who has been kidnapped. For some reason (we find out later it’s because Nick is the girl’s long lost father), only Nick can see Happy.

Grant Morrison’s Happy! is an odd little comic (now adapted to a TV series on SyFy) about a former-cop-turned-hitman Nick Sacks who, after a particular hit, finds himself pursued by powerful people believing that he has a password belonging to a deceased (but very rich) don. After the hit at the beginning of the story, he has a heart attack and now finds himself seeing an imaginary blue unicorn named Happy. Happy is the imaginary friend of a young girl named Haley, who has been kidnapped. For some reason (we find out later it’s because Nick is the girl’s long lost father), only Nick can see Happy.

This story is full of Christmas imagery, albeit dark and twisted imagery, with a drunk doped up Santa who kidnaps kids (like Haley) for a child porn ring and a Christmas tree with those same children wrapped up and waiting to be “opened” like Christmas gifts.

The story unfolds with Happy attempting to convince Nick that he’s real, which he successfully does by helping him cheat during a game of poker. The story captures the tension between Nick’s cynicism and hopelessness and Happy’s unrelenting sense of joy and hope.

In his frustration, Nick takes Happy on a journey to see the dark underbelly of the real, and to Morrison and Robertson’s credit, they show us a pretty sick world that is more like ours than we’d like to admit. The “real” world of Nick Sacks is a dark and gritty world, where lovers who a moment ago were making goo-goo eyes at each other turn on each other, yelling that they hate each other. Where a man on the phone yells at his wife who accuses him of an affair. Where people are verbally cannibalizing each other.

In this way, one sees in Happy! one of the themes that permeates Morrison’s writings, the juxtaposition of the real-world nihilism with the hope of imagination and heroes. We can bring our imagined hopes into the “real” world and make it better. As Happy tells Nick, “You think I don’t know it’s a cruel, rotten world? I may be an ugly, stupid looking ass, Nick, but I’m hope. All singing, all dancing—hope. Doing my best to brighten up the old graveyard while you whine and moan….”

In other words, there is a hope beyond the bare facts of the world. We are able to imagine a better, more just world, where evil, cruelty and perversity don’t rule unchallenged.

Toward the end of the story, Nick confronts the crazy Santa and his boss, Mr. Blue, who tells Nick that it’s people like him who run the world, powerful and cruel (usually) men, who don’t think for a second about engaging in despicable acts like child porn in order to cement their own riches and power or slaughtering those same children.

And this is why I think Happy! is an odd but spot-on Advent story. For Christians, Advent celebrates the coming of the Christ child, whose very coming puts the cruel and powerful rulers of the world on notice. It even includes the story of another powerful man who rules the world and slaughters children to cement his own power (we’re looking at YOU Herod the Great). Even if that story isn’t historical, it reflects an idea about how the powerful in this world operate.

In Happy!, the corrupt men who rule the world our overcome with the irruption of hope into the grim and gritty world, as Happy shows up to the rescue with an army of other imaginary friends to save Nick and the children.

And this is the idea behind Advent, that a hope beyond the bare facts of the world, that one can only imagine, has broken into our “real” world, with its cruelty, cynicism, and injustice, and has called it to account. The words of Mary the mother of Jesus ring true as much in Christian tradition as they do in Happy!:

He has shown strength with his arm.

He has scattered those with arrogant thoughts and proud inclinations.

He has pulled the powerful down from their thrones and lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty-handed. (Luke 1:51-53, CEB).

As I said, Happy! is an odd little story, but it is a Christmas story, and it captures something special about the Advent message. God has shown strength beyond the strength of this world. He has done so on behalf of the oppressed. And the Mr. Blues of this world are sent away empty-handed and brought down from their thrones.

Those without a prayer now have one. Those without hope now have a hope against hope.

At one point in the story, Happy disappears and Nick is left alone to wonder what he should do. He wanders into a Catholic church. There’s a bit of irony in Nick’s comment when he first walks in that “there’s no one here.” Nick finds the priest in the backroom, and while he desperately asks the priest to give him guidance, he notices something on the laptop of the priest—a link to the kiddie porn site featuring Haley and the other children.

Although this seen portrays a painful reality we are all familiar with, the hypocrisy of spiritual leaders who claim to represent God’s interests on earth, the fact that Nick feels compelled to go to the church and finds out where the children are causes us to ask maybe there is a God who mysteriously acts through mysterious signs and visions to guide the world toward justice. All of this, despite the reality that many of our spiritual leaders are caught up in scandals and collaborate with the forces of empire to impede justice and further corrupt the world.

In spite of all of that, there is Advent. There is a God who speaks into the world. And gives us hope. Advent reminds us that even when our government fails us. The economy fails us, or even our trusted spiritual guides fail us, hope can still break into this corrupt world and upend the powerful and expose the wickedness that thought it could remain hidden.

And bring justice and deliverance for those who were merely “hoping” for it.

That make me happy!

Matthew William Brake is the creator and founder of Pop Culture and Theology and the series editor for the book series Theology and Pop Culture from Lexington Books. He holds degrees in Interdisciplinary Studies and Philosophy from George Mason University and a Master of Divinity from Regent University. He has published numerous articles in the series Kierkegaard Research: Sources, Reception, Resources. He has chapters in a number of books on philosophy and pop culture, including Deadpool and Philosophy, Wonder Woman and Philosophy, and Mr. Robot and Philosophy.