In a piece last year for Nomos Journal, I explored how the ancient Greek myth of the Cyclops compared in Homer’s Odyssey to the modern graphic novel The Encyclopedia of Early Earth by Isabel Greenberg (December 2013). Homer’s account became the definitive text in the West for the mythical concept as well as the hypothetical, physical characteristics of this creature. As I argued in that piece, however, whenever a myth gets re-appropriated and re-produced by a different culture, it is subject to modification. While some see a loss of the original “essence” of a myth, others view this change as a positive thing insofar as it is by this modification that myth remains dynamic and relevant for a different people and time.

In a piece last year for Nomos Journal, I explored how the ancient Greek myth of the Cyclops compared in Homer’s Odyssey to the modern graphic novel The Encyclopedia of Early Earth by Isabel Greenberg (December 2013). Homer’s account became the definitive text in the West for the mythical concept as well as the hypothetical, physical characteristics of this creature. As I argued in that piece, however, whenever a myth gets re-appropriated and re-produced by a different culture, it is subject to modification. While some see a loss of the original “essence” of a myth, others view this change as a positive thing insofar as it is by this modification that myth remains dynamic and relevant for a different people and time.

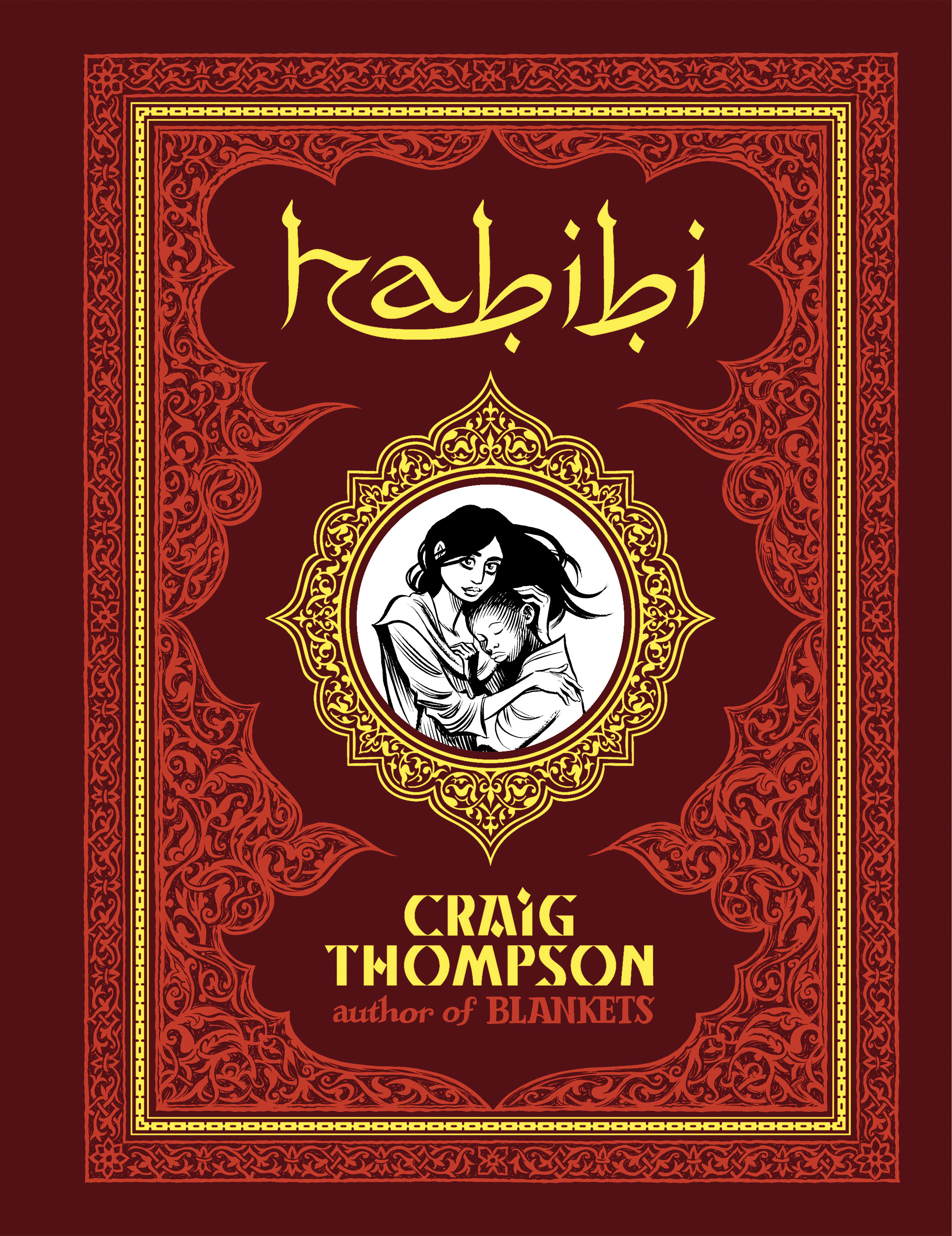

The graphic novel is a prime example of how ancient stories remain relevant for a modern audience. The explosion in graphic novel production in recent years has given us plenty of data for the types of modifications that occur in these ancient myths. By investigating which types of modifications occur, we can find out what particular cultures value, and what they do not. Elements of ancient myth that conform to modern values will be retained or strengthened, in other words, while elements of ancient myth that are irrelevant to modern culture and sensibility will be minimized or removed. With an attention to what is retained/removed and highlighted/diminished between the two permutations of a given myth, we can identify more concretely different cultural values.

It was with this understanding that I compared Homer’s Cyclops Polyphemus to Greenberg’s graphic novel depiction of the Cyclops in her own imaginative re-telling of parts of the The Odyssey. It turned out that, save for some basic characteristics in form (large, monstrous, and one eye) and landscape (seemingly isolated and generally undeveloped), the episodes were hugely different. There was no dialogue in Greenberg, no contrast between a civilized, social Greek (Odysseus) and an uncivilized or minimally civilized solitary brute (Polyphemus).

The episode in Homer revolved around the concept of hospitality, a socially constructed obligation that Polyphemus flouts and thereby rejects society. Homer also focused on the combination of teamwork and cunning in Odysseus’s escape, two characteristics that defined what it meant to be a citizen in Greek democratic society. Greenberg’s hero uses no teamwork, no cunning, and escapes purely through humorous, dumb luck as a bird poops in the Cyclops’s eye, thereby giving the protagonist time to escape. Greenberg’s hero is a ‘better lucky than good’ protagonist on an individual quest for romantic love, a distinctly modern concept.

Compared to Homer’s Odysseus, Greenberg’s hero – with a romantic goal, lucky escape, lack of crewmates, and lack of socially constructed value such as hospitality – fully reflects modern, Western culture’s value of individualistic identity over and against Homeric Greece’s socially constructed identity.

But there is another prominent Cyclops in the modern graphic novel, the Scott Summers of Marvel Comics’s X-Men fame. If my above argument is correct, that Greek concepts of socially structured identity become effaced when translated into modern culture, we should expect that a comparison of Homer’s Polyphemus and Marvel’s Cyclops yields the same result: some core similarities in terms of physical form, perhaps, but large-scale differences in interactions and identity. Continue reading Cyclops in Homeric Myth and Marvel Comics