There are many different angles from which to consider comic book Bibles and plenty of excellent scholarship already shared on Sacred and Sequential. I don’t intend to go over this ground again but instead to consider comic Bibles from the perspective of Religious Education pedagogy; what might educators need to consider before they bring comic book Bibles into the classroom as materials for study and learning. I am not concerned therefore, with comics as tools for evangelising or as supposed miracle cures for reluctant readers. Instead I am coming from the perspective of English mainstream education where Religious Education is a legal requirement. Of course, this is a situation that is not always present in other countries but hopefully I can stir up useful questions and pedagogical judgements that should surround our classroom materials used by all students, regardless of the medium. Or encourage you to think about using comics in your classrooms, because I really think they are a fantastic, much under-appreciated resource!

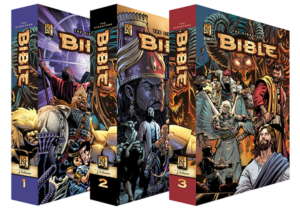

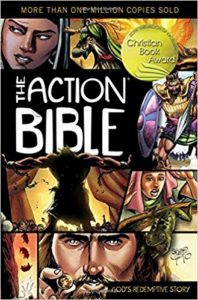

Typically most single-volume English-language comic Bibles, for example the Action Bible (2010) include Old and New Testaments but group, skip and reorder the narratives rather than reflecting the canonical books. Such comic Bibles are almost always devoid of chapter and verse references alongside the panels so the reader has no easy way to connect what they are reading to the monotextual source, nor necessarily even know that they are reading a modified narrative. For example, often the Song of Solomon/Song of Songs and the book of Job are omitted. The story of Jesus is always retold in a single, un-nuanced narrative rather than the individual, sometimes contradictory Gospels. I am yet to find a comic Bible that presents all four Gospels separately – if you know of any, let me know! Furthermore, very rarely do the comic creators or publishers explicitly reference which monotextual translation or translations they have used as the source text. As such, educators are left to make their own judgements as to the scholarly merit of the translation rather than being able to evaluate it with reference to known credible works. In these respects also, students are not able to engage with the notion of the Bible as a text compiled and contested over time. Whilst almost all comic Bibles leave some events out, few also try to cram too many narrative threads into a single place. For example, The Lion Graphic Bible (2001) and The Hero Bible (2015) give Jesus all three versions of his final words from the Gospels to deliver in a single panel. Again, without citing their sources this leaves no room for reflective engagement with the contested nature of the texts and of course, two of the three cease to be a final utterance.

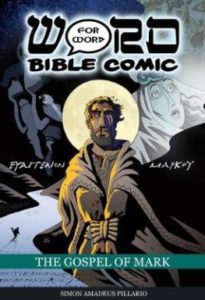

An exception is the ongoing work of Simon Amadeus Pillario. His The Book of Judges: Word for Word Bible Comic (2016), The Book of Ruth (2016), Gospel of Mark (2018) and the forthcoming crowd-funded The Book of Esther are illustrated in a conscious effort to be as historically accurate as possible as well as keep every word from the source text (World English Bible). Visually I found them quite hard work to read (a matter of personal choice, nothing more) and because of the limited print run, expensive to buy. As such, I have not considered them for use in my classroom although they would suit those with healthier budgets!

Similar to Pillario, Alex Webb-Peploe andAndré Parker have produced sections of the Bible as stand alone comic books; A Light in the Darkness (2014) and The Third Day (2014). However they make the bold claim that the narrative has been unchanged. Webb-Peploe and Parker even go so far as to credit Luke as the author of the comics. This serves as an important reminder of the complex nature of authorship. How should we best refer to those involved with comic book Bibles; are they creators, compilers or something else? Does the very act of assigning credit on the front cover serve to differentiate a comic Bible for students from the comparably authorless monotextual Bible?

Webb-Peploe and Parker present the birth and death of Jesus as isolated narratives with the text sourced solely and unaltered from Luke’s gospel in the NIV of the New Testament. In this way, a reader familiar with the popular versions of the Christmas and Easter stories (as most young people in the UK are to some degree) are confronted with the discrepancies between Biblical and popular culture accounts in a way that continuous narrative comic Bibles cannot. The artists write that theirs is “a historical account, so we haven’t added or changed anything, and we’ve taken great care to bring these remarkable events to life as faithfully as we possibly can” (Webb-Peploe and Parker 2014). Except modern scholars would argue that the author of Luke is unknown and that the author drew from a variety of sources including Mark’s gospel and the Q source. Further, such a bold claim is really problematic when taking something from a monotext and adding images; the very act of rendering a narrative as image/text changes it, the role of the reader, and the information that is being conveyed. There is a reason we love studying comics as opposed to other mediums and boldly claim that they are doing ‘something different’! The artists give the narrator, ‘Luke’ a face for example and of course in all the examples of comic Bibles Jesus is shown. This is a stark example of the challenges that come with transforming the Bible into image/text; creators have to make choices about the depiction of the divine, of geography and historicity, all of which can enhance or become barriers to the readers’ engagement. So The Third Day is scripturally the most faithful adaptation in its text but arguably falls the furthest from its own standards, tripped up by addition of images. Nonetheless, these issues could present valuable learning opportunities should the teacher wish.

Finally it is worth briefly considering the degree to which the medium of comics and their relationship to secular, popular culture, influences the perception of scriptural authority. Regardless of the perspective from scholarship, crucial to the classroom is any hierarchy that the individual student and any faith community or doctrine they are connected with, might impose. In this respect, it would be naïve to assume teachers or students will automatically confer sacred and scriptural authority on a comic book Bible used in the classroom. However, some degree of authority may come with their status as pedagogical materials introduced by a teacher. Although if this is perceived to be a solely secular authority the student may find themselves in an uncomfortable position that requires them to function in and between two, separate and competing worldviews. This kind of discomfort is acknowledged and to a degree understood as edifying within the field of Religious Education in England although it may not be in other settings.

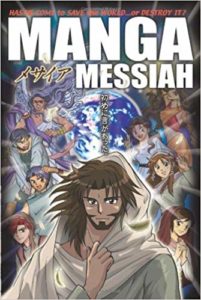

In the end, I chose Manga Messiah (2007) for my classroom. Siku’s The Manga Bible (2007) is of an equal standard but the style of illustration is quite sparse and severe and so more of an acquired taste (for the record, I adore it). Manga Messiah contains chapter and verse references on each page and follows the narrative and speech turns of the NRSV closely (although it does not directly cite a translation). The text includes Hebrew terms such as Rabbi and Levite. Each panel composition reflects the third-person narrative perspective of the monotextual Bible and the illustration style shifts slightly to signify the Parables. The story-within-story dimension of the Parable is reflected in this simplified line style and black gutters, which demarcates it in a manner a monotextual source never could.

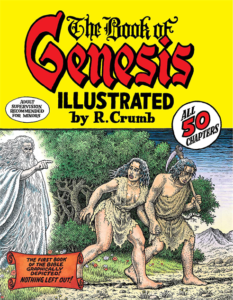

[For comparison, enjoy this 2014 Sacred Matters article, The Bible in Comics: Genesis, by Beth Davies-Stofka.]