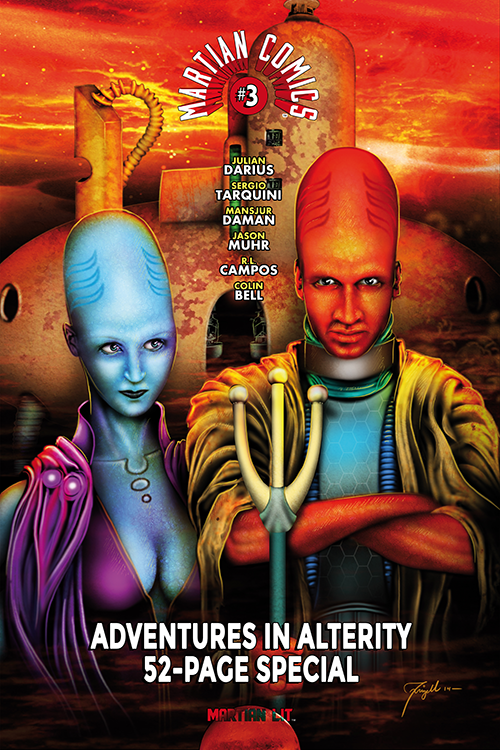

![]() This past month, Sacred and Sequential had the opportunity to chat with Julian Darius, President & Founder of the Sequart Organization and creator of Martian Comics from his own Martian Lit imprint. With the release of the Kickstarter-funded Martian Comics #3 and its intriguing religious content, he talks with us about the wide range of thinking behind his (not-so-)alien tales.

This past month, Sacred and Sequential had the opportunity to chat with Julian Darius, President & Founder of the Sequart Organization and creator of Martian Comics from his own Martian Lit imprint. With the release of the Kickstarter-funded Martian Comics #3 and its intriguing religious content, he talks with us about the wide range of thinking behind his (not-so-)alien tales.

S&S: Before we focus on the most recent Martian Comics #3, perhaps you could outline what “Martian Mythology” is and what was involved in producing these works?

JD: The “Martian mythology” is essentially the backstory of the whole series. Back when I founded Martian Lit, I thought it would be funny to have it actually run by Martians, and I worked up this backstory of planetary orders, an enlightenment program (that included Jesus and others), the cloaking of Mars’s cities, and the sort of vague threat that the Martians are still debating and split over whether to invade. There was a lot of detail for what was essentially a complex joke.

When Kevin Thurman pitched me on what became “The Girl from Mars,” it was wedded to this backstory I’d worked up for Martian Lit. As we collaborated on the early “Girl from Mars” chapters, I began expanding this backstory and writing these other Martian stories. It’s kept growing. It’s really because of this that the series is called Martian Comics — a throwback to titles like Adventure Comics and whatnot — and wasn’t titled The Girl from Mars. Initially, “Martian mythology” was a way of separating this backstory I’d created and was exploring in these side stories from “The Girl from Mars.” “Martian mythology” is kind of the backbone of the series — “The Girl from Mars” is the first story, the first window into that mythology.

But this “Martian mythology” has kept growing. There’s a map of stories waiting to be told, whole arcs of Martian history, ways in which themes echo throughout the stories and into the various more narrow stories, like “Girl from Mars.” It’s a pretty vast thing, which I’ve kind of put together over the past several years and keep adding to.

Continue reading The Martian Chronicles of Julian Darius, Part I

Continue reading The Martian Chronicles of Julian Darius, Part I

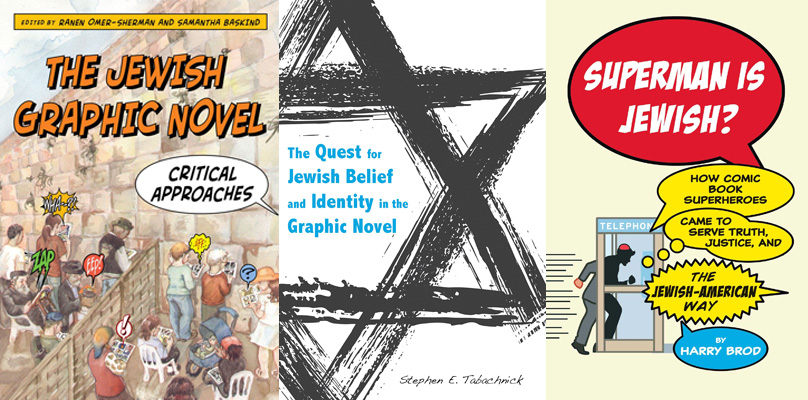

Anderman discusses several Jewish-content graphic books in the article. However, many of these are several years old. It is impossible to list off every Jewish graphic novel in such a short piece, but one would hope that the most recent publications would have been included. Hereville : How Mirka Caught a Fish recently won the 2015

Anderman discusses several Jewish-content graphic books in the article. However, many of these are several years old. It is impossible to list off every Jewish graphic novel in such a short piece, but one would hope that the most recent publications would have been included. Hereville : How Mirka Caught a Fish recently won the 2015